The Internet was alive earlier this year with discussions surrounding diversity and the film industry. A UCLA report covered by the THR in March published an alarming statistic: female writers only accounted for 12.9 % of all Hollywood screenwriting. That means that in 2015 men still make up nearly 90 % of all writing generated in Hollywood. More recent press coverage of unequal pay in the film industry in general and in Hollywood in particular made me revisit these figures, and then it got me thinking about the presentation of female writers in Hollywood film – specifically in the classic Sunset Boulevard (Wilder, 1950).

As well as being a send-up of the Hollywood studio system, the film is all about reading and writing. Sunset Boulevard paints a picture of a divided world: divided into readers and writers, and men and women. And at first glance, women are presented as passive (readers), while men write (actively). The narrator, Joe Gillis, is a screenwriter down on his luck. Nevertheless, he seems to be producing, churning out, he tells the viewer, up to two stories a week. The readers’ room at Paramount Studios, by contrast, is personified by Betty Schafer – a young woman who failed as an actress before becoming a reader; and then, of course, there is Norma Desmond (the film’s protagonist, an ageing star from the silent film era) who is so incapable of producing writing that she has to engage the help of Gillis in order to complete her epic screenplay, Salome. Schafer too asks for Gillis’ help to co-author a screenplay because, she states, she is ‘just not good enough’ to do it alone. A half eaten apple-core in the bottom left hand corner of the shot seems to wryly comment on this positively biblical separation of gender roles in the studio system.

Yet, observed more closely, the film presents a much more nuanced picture. It can even be read as a subversive interrogation of these reader/writer roles. Betty Schafer might be employed as a reader, but she is really a talented writer who is forced to read. Gillis, on the other hand, talks a great deal about writing. He is, however, driven not by the written word, but by the acquisition of capital. He is not a writer; he is a gigolo. Gillis in his voiceover presents Norma as a grotesque – a figure to be pitied and despised. However, the mere fact that Gillis narrates the story in voice-over constantly foregrounds points of view, and implicitly questions his presentation of events. In fact, Norma always remains in a position of power; even when the dialogue puts dramatic expressions of her own weakness into her mouth. After all, she has money and Gillis is destitute; he is a lodger in her home, constantly at her beck and call; and, most importantly, she is writing and he is reading her work.

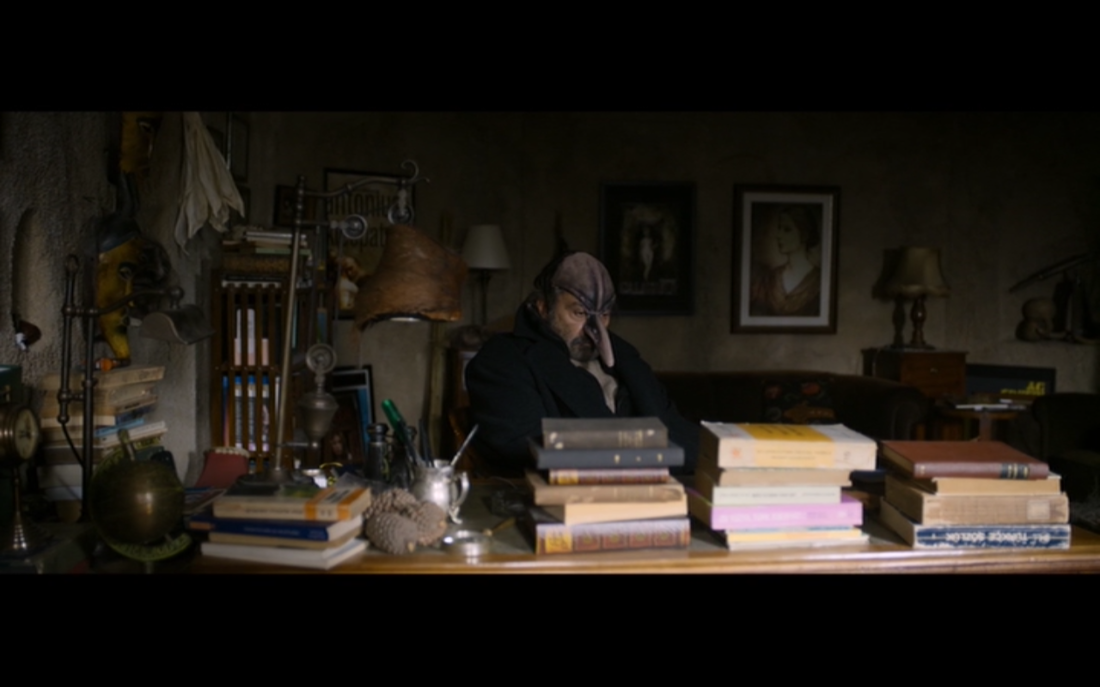

More interesting than this division of the world into readers and writers, women and men, however, is the presentation of Norma Desmond: as a writer and an ageing woman in Hollywood. How and why does a woman like Norma write? The mode of production seems to be important. At the heart of Norma Desmond as a character is the autograph – the hand-written word. The film explores the distinction between machine writing (typing) and handwriting. Handwriting is aligned with the past and is associated with amateurs. It is linked to a bygone period with bygone stars. Like Norma, handwriting is an anachronism, replaced by more modern methods. In fact, it is scorned by Gillis, who uses the word ‘scrawl’, clearly expressing his disdain not only for Norma, but also for handwriting in general. Professional writers and young people have moved on to more modern modes of writing production. The process has become industrialised. Both Gillis and Betty Schaefer use typewriters. Norma, by contrast, has written her script of Salome by hand, in a spidery script, on thick sheets of parchment. It is interesting that Gillis calls her handwriting a ‘childish’ scrawl, when throughout the film it is Norma’s age, her association to death, and her maturity that he finds most repugnant.

But handwriting, for Norma, is more than just a link to the past and to history. It is a question of identity. The actress spends a great deal of time signing pictures for fans by hand. She is constantly autographing. Her manuscript becomes an extension of this autographing process. The bundles of papers she tells Gillis she has been working on for years look like love letters. For Norma, writing is very personal: by hand-writing she walks the line between the self and the fiction. And she uses writing to create a more active role for herself in life. She writes herself as Salome.

Another layer to this auto-fictionalisation is applying make-up, which can be seen as another kind of handwriting. In one of the film’s most striking and painful scenes we watch Norma writing on her own body, preening and mummifying, perfecting: crafting her own image – writing on skin. By the end of the film, we feel that she has written Salome onto herself and inhabits her. Her life has become her fiction. Whereas the biblical Salome is condemned for her role as a murderous harlot, Norma is portrayed as a human being, with passion, trapped in a system that has no place for her. Writing, for Norma, means writing herself back into the history of Hollywood. And, in a manner of speaking, she succeeds. Of all the failed writers in Sunset Boulevard, she comes closest to self-actualisation, to getting her script made. Not only does she re-enact the final scene of her script for the paparazzi that come to watch her arrest after Gillis’ murder. Indeed, she has already played out the storyline of her script – for the plot of Sunset Boulevard itself is a story of an ageing Salome. And while the legal system condemns her, the viewer’s response is less clearly defined. It is particularly poignant that the film allowed Gloria Swanson (a silent actress whose own career had really been dead in the water since the advent of sound) to work again, in a leading role, in a major Hollywood production. Life and art in Sunset Boulevard imitated each other.

What if Norma has been allowed to write her epic for Paramount? I would have liked to see it. Sadly, her script belongs to fiction not history. Yet, in the absence of this mythic screenplay, Sunset Boulevard is a fitting stand-in, an open and complex exploration of the world of Hollywood fictions, writing, and gender, and one that remains relevant today.

As well as being a send-up of the Hollywood studio system, the film is all about reading and writing. Sunset Boulevard paints a picture of a divided world: divided into readers and writers, and men and women. And at first glance, women are presented as passive (readers), while men write (actively). The narrator, Joe Gillis, is a screenwriter down on his luck. Nevertheless, he seems to be producing, churning out, he tells the viewer, up to two stories a week. The readers’ room at Paramount Studios, by contrast, is personified by Betty Schafer – a young woman who failed as an actress before becoming a reader; and then, of course, there is Norma Desmond (the film’s protagonist, an ageing star from the silent film era) who is so incapable of producing writing that she has to engage the help of Gillis in order to complete her epic screenplay, Salome. Schafer too asks for Gillis’ help to co-author a screenplay because, she states, she is ‘just not good enough’ to do it alone. A half eaten apple-core in the bottom left hand corner of the shot seems to wryly comment on this positively biblical separation of gender roles in the studio system.

Yet, observed more closely, the film presents a much more nuanced picture. It can even be read as a subversive interrogation of these reader/writer roles. Betty Schafer might be employed as a reader, but she is really a talented writer who is forced to read. Gillis, on the other hand, talks a great deal about writing. He is, however, driven not by the written word, but by the acquisition of capital. He is not a writer; he is a gigolo. Gillis in his voiceover presents Norma as a grotesque – a figure to be pitied and despised. However, the mere fact that Gillis narrates the story in voice-over constantly foregrounds points of view, and implicitly questions his presentation of events. In fact, Norma always remains in a position of power; even when the dialogue puts dramatic expressions of her own weakness into her mouth. After all, she has money and Gillis is destitute; he is a lodger in her home, constantly at her beck and call; and, most importantly, she is writing and he is reading her work.

More interesting than this division of the world into readers and writers, women and men, however, is the presentation of Norma Desmond: as a writer and an ageing woman in Hollywood. How and why does a woman like Norma write? The mode of production seems to be important. At the heart of Norma Desmond as a character is the autograph – the hand-written word. The film explores the distinction between machine writing (typing) and handwriting. Handwriting is aligned with the past and is associated with amateurs. It is linked to a bygone period with bygone stars. Like Norma, handwriting is an anachronism, replaced by more modern methods. In fact, it is scorned by Gillis, who uses the word ‘scrawl’, clearly expressing his disdain not only for Norma, but also for handwriting in general. Professional writers and young people have moved on to more modern modes of writing production. The process has become industrialised. Both Gillis and Betty Schaefer use typewriters. Norma, by contrast, has written her script of Salome by hand, in a spidery script, on thick sheets of parchment. It is interesting that Gillis calls her handwriting a ‘childish’ scrawl, when throughout the film it is Norma’s age, her association to death, and her maturity that he finds most repugnant.

But handwriting, for Norma, is more than just a link to the past and to history. It is a question of identity. The actress spends a great deal of time signing pictures for fans by hand. She is constantly autographing. Her manuscript becomes an extension of this autographing process. The bundles of papers she tells Gillis she has been working on for years look like love letters. For Norma, writing is very personal: by hand-writing she walks the line between the self and the fiction. And she uses writing to create a more active role for herself in life. She writes herself as Salome.

Another layer to this auto-fictionalisation is applying make-up, which can be seen as another kind of handwriting. In one of the film’s most striking and painful scenes we watch Norma writing on her own body, preening and mummifying, perfecting: crafting her own image – writing on skin. By the end of the film, we feel that she has written Salome onto herself and inhabits her. Her life has become her fiction. Whereas the biblical Salome is condemned for her role as a murderous harlot, Norma is portrayed as a human being, with passion, trapped in a system that has no place for her. Writing, for Norma, means writing herself back into the history of Hollywood. And, in a manner of speaking, she succeeds. Of all the failed writers in Sunset Boulevard, she comes closest to self-actualisation, to getting her script made. Not only does she re-enact the final scene of her script for the paparazzi that come to watch her arrest after Gillis’ murder. Indeed, she has already played out the storyline of her script – for the plot of Sunset Boulevard itself is a story of an ageing Salome. And while the legal system condemns her, the viewer’s response is less clearly defined. It is particularly poignant that the film allowed Gloria Swanson (a silent actress whose own career had really been dead in the water since the advent of sound) to work again, in a leading role, in a major Hollywood production. Life and art in Sunset Boulevard imitated each other.

What if Norma has been allowed to write her epic for Paramount? I would have liked to see it. Sadly, her script belongs to fiction not history. Yet, in the absence of this mythic screenplay, Sunset Boulevard is a fitting stand-in, an open and complex exploration of the world of Hollywood fictions, writing, and gender, and one that remains relevant today.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed