Writing is a losing game. Writing anything – other than say, a very short shopping list – can sometimes feel like an orgy of self-delusion. Weaving together what one thinks is a tapestry of text, only to be confronted by a scarf full of holes where you missed the stitches. Once completed, no matter how much time you’ve invested in it, you always feel you could have done more, better, and differently. And if you don’t, then someone else almost certainly will. Wouldn’t it be better if it were about something else, somebody else, or took place somewhere else? Wouldn’t it sound better if you had written it in French? Wouldn’t it be better, come to think of it, if you had never started it at all? You could have saved yourself the trouble. And what a lot of trouble. For, while endings and middles are sometimes confounding, there is nothing quite like the exquisite agony of beginning. A lonely vowel or consonant—an empty sign on a blank page. The beginning of a journey. One letter, and in it an infinite possibility, leading to one possible outcome: disappointment.

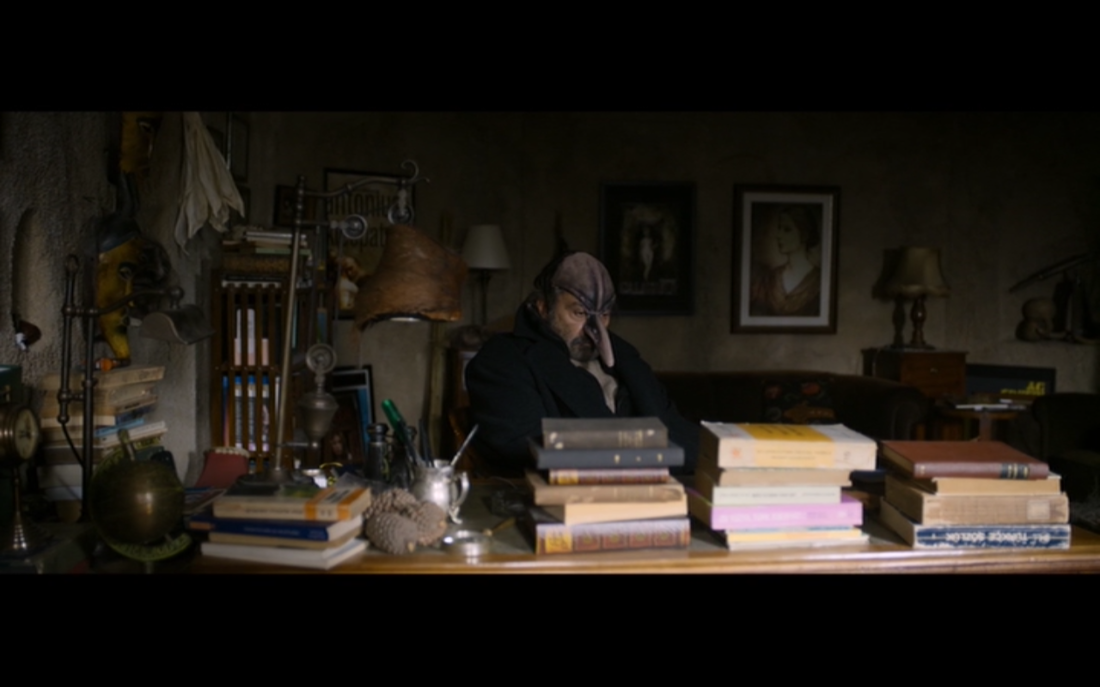

In the 2014 film 'Winter Sleep', the protagonist Aydin (a retired actor who runs the hotel 'Othello') doesn’t even start his book, a book he talks about writing throughout the film, until the film’s final scene. Why doesn’t Aydin start? What holds him back? Fear of failure? Fear of success? Fear of himself? Boredom? Whatever the cause behind his faltering, Aydin’s great 'History of Turkish Theatre' is a book caught up in an endless beginning. Quite apart form a beautiful metaphor embodying the socio-political experiences of a nation, the film is an observation of the act of writing, or rather, the act of failing to write.

We watch and become engrossed in a series of moments before the great dramatic moment. We are caught in a cinematic preamble to something. The beautiful, snow-covered landscape of Cappadocia becomes a visual poem to disappointment and frustrated beginnings. Because, of course, once that vowel is down on the paper, or out there on the screen, once you have agonised over starting, whatever comes next can only be fulfilled potential – and potential fulfilled is necessarily a disappointment.

So what is the point? Why write? After all, by the time Aydin begins writing his 'History of Turkish Theatre', he has already lived it: generational conflict; the social guilt that comes with land ownership; charity; morality; conscience; broken relationships; a journey to Istanbul which Aydin almost undertakes, getting no further than the local train station. In short, life happened while the writer was busy making plans to write. Yet false starts are, both on the level of plot and existentially speaking, what it’s all about. The film revels in them: almosts and not quites. Aydin is almost a good person, but not quite. His wife is too. They are almost conscious of social wrongs and almost unselfish. They are almost happy, but not quite. They are almost honest with each other. But not quite. They almost understand each other and the world around them. But not quite. Aydin is almost writing a great work on the Turkish theatre. But not quite.

This obsession with unfulfilled potential and journeys that end before you even board the train, this persistence on almost, means that the beginning, when it finally comes (even if it is, chronologically speaking, the end) feels redemptive. After all, the first vowel, the first consonant, they hold within them the complete works of Shakespeare. Either that or nothing at all. Usually they contain nothing at all. But it is curiously comforting to think that all possible words are wrapped up in that one sign. Everything comes before that first letter and something will follow it. That first letter – and after it the first sentence – is the textual equivalent of opening your eyes. After a winter sleep. Even if what you see isn’t quite what you’d hoped for, isn’t it better than nothing at all?

In the 2014 film 'Winter Sleep', the protagonist Aydin (a retired actor who runs the hotel 'Othello') doesn’t even start his book, a book he talks about writing throughout the film, until the film’s final scene. Why doesn’t Aydin start? What holds him back? Fear of failure? Fear of success? Fear of himself? Boredom? Whatever the cause behind his faltering, Aydin’s great 'History of Turkish Theatre' is a book caught up in an endless beginning. Quite apart form a beautiful metaphor embodying the socio-political experiences of a nation, the film is an observation of the act of writing, or rather, the act of failing to write.

We watch and become engrossed in a series of moments before the great dramatic moment. We are caught in a cinematic preamble to something. The beautiful, snow-covered landscape of Cappadocia becomes a visual poem to disappointment and frustrated beginnings. Because, of course, once that vowel is down on the paper, or out there on the screen, once you have agonised over starting, whatever comes next can only be fulfilled potential – and potential fulfilled is necessarily a disappointment.

So what is the point? Why write? After all, by the time Aydin begins writing his 'History of Turkish Theatre', he has already lived it: generational conflict; the social guilt that comes with land ownership; charity; morality; conscience; broken relationships; a journey to Istanbul which Aydin almost undertakes, getting no further than the local train station. In short, life happened while the writer was busy making plans to write. Yet false starts are, both on the level of plot and existentially speaking, what it’s all about. The film revels in them: almosts and not quites. Aydin is almost a good person, but not quite. His wife is too. They are almost conscious of social wrongs and almost unselfish. They are almost happy, but not quite. They are almost honest with each other. But not quite. They almost understand each other and the world around them. But not quite. Aydin is almost writing a great work on the Turkish theatre. But not quite.

This obsession with unfulfilled potential and journeys that end before you even board the train, this persistence on almost, means that the beginning, when it finally comes (even if it is, chronologically speaking, the end) feels redemptive. After all, the first vowel, the first consonant, they hold within them the complete works of Shakespeare. Either that or nothing at all. Usually they contain nothing at all. But it is curiously comforting to think that all possible words are wrapped up in that one sign. Everything comes before that first letter and something will follow it. That first letter – and after it the first sentence – is the textual equivalent of opening your eyes. After a winter sleep. Even if what you see isn’t quite what you’d hoped for, isn’t it better than nothing at all?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed